Columnist Tolley M. Jones: Soon ah will be done with the troubles of the world

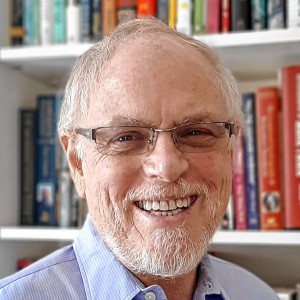

Tolley M. Jones

| Published: 04-10-2025 7:01 AM |

“Soon ah will be done with the troubles of the world, goin’ home to live with God”

Negro spirituals are the heart, soul, anguish and hope of those suffering the worst pain, heartache and inhumane treatment at the hands of those white men and women who filled their hearts with the irreversible taint of slavery. Black enslaved men and women sang so continuously that their music shaped the entire musical fabric of America to this day. Our music is haunting, felt in vibrations on your skin and dripped onto your tongue, and embeds itself into the rhythm of your own heartbeat. Our songs on the surface spoke of the Christian hope of eternal salvation in heaven after death. But that is not what the songs are really about.

Negro spirituals are coded songs that were a heartbeat of collective resistance and hope, and a fierce refusal to let the human animals who worshipped profit and power over basic human compassion and any semblance of the Christianity they pretended to espouse, triumph over the souls of the enslaved. White enslavers pretended to believe that enslaved Blacks singing in the field were evidence that they were happy, yet took great pains to regulate what songs and instruments the enslaved were permitted. They fundamentally understood the steely and unfettered potency embedded in those songs, and feared that enslaved Blacks would harness the power of their music and rise up in a terrifying display of justified retribution.

“No more weepin’ and wailing, goin’ home to live with God”

The thing is, if you take people away from their families, their homes, and separate them from all the things that define them as humans, they then have nothing left to lose, and that is a dangerous line to walk for white colonizers, enslavers, and fascists. Harriet Tubman said “I had reasoned this out in my mind, there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; If I could not have one, I would have the other.”

Yet time and time again, white people convince themselves that the world will eternally provide them with an endless supply of weak and lesser humans to exploit for their own profit, enjoyment, and petty egotistical commitment to the delusion that they are superior and therefore entitled to treat everyone else with contempt and inhumanity. Those who raped, tortured, and dehumanized our Black enslaved ancestors spawned those who brought their white children to picnic and frolic at the stiff and dangling feet of lynched Black humans, urging those children to scramble for bloody scraps of flesh to wield as gruesome souvenirs to celebrate their depravity. And those children begat those who now celebrate an eagerly anticipated return to when white people could cut open an uppity Black woman and stomp her fetus to a bloody pulp with impunity because they thought that rights are to be doled out at the whim of those who could buy the privilege. They resent the fact that they themselves have been deprived of the joy of collecting Black body parts at a festive lynching of Black people whose only offense was existing within the monstrosity of white bigotry.

The United States is now on a fast and eager slide toward fascism, yet Black people are home singing and dancing as we always have been for hundreds of years. We do not celebrate the impending horrors that will certainly fall with crushing and disproportionate severity on all of us with brown and Black skin, as has always been the case when white people fear the exposure of their mediocrity and the true smallness of their power. No, we sing because we have sung this song before, many, many, many, times before. Our songs were composed as an indelible form of immutable resistance that white people could not and cannot erase. The songs are in our heads, our hearts. We sing the songs of our enslaved ancestors to summon them, and that is what you hear when we sing. And that is what you hear when we are silent.

White people know we may be standing silently but we are singing songs of resistance in our head, and every other Black person is singing the same song. What a fearsome thought for those who only hold external and fleeting power. They cannot understand how we can still know the songs of our ancestors and sing them with the same collective knowledge and strength. How can we still remember every inflicted injustice when white people think they have dominion to rewrite history to whitewash their bloody hands? The potency of our music and songs is frightening to them because it is the musical evidence of what true freedom and power is.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Report cites inequities in land valuation for central, western Massachusetts

Report cites inequities in land valuation for central, western Massachusetts

Amherst Town Council calls emergency meeting to consider rescinding funds for Jones Library project

Amherst Town Council calls emergency meeting to consider rescinding funds for Jones Library project

Hadley man detained after chemicals go missing

Hadley man detained after chemicals go missing

Student petition leads Amherst Regional High to reopen bathrooms during lunch; school will explore other ways to address vaping

Student petition leads Amherst Regional High to reopen bathrooms during lunch; school will explore other ways to address vaping

Columnist Bill Newman: The war on us has begun

Columnist Bill Newman: The war on us has begun

Turnover coming for Northampton School Committee

Turnover coming for Northampton School Committee

White people throughout history fear the long memory Black people have encoded in our very DNA, unfazed and unaffected by digging out superficial pavement monuments, deletion of pictures and written records of the vast and astounding accomplishments of our people. They dread the immovable and permanently damning evidence we carry within us of white people’s sins against our humanity. They take away our drums in fear, and we beat out the rhythm of our homelands and the cadence of our power on our very bodies.

Despite white people’s constant and desperate attempts to wipe out the evidence of our existence and the inextricable reality of the blood that stains their hands in a permanent stigma of moral disgrace and desolation, our songs live in our hearts and souls and we sing them with damning collective consciousness, for our history cannot be erased and our power is not within the reach of those who fear it.

“When I get to heav’n I will sing and tell

How I did shun both death and hell”

Tolley M. Jones lives in Easthampton. She writes a monthly column.

Guest columnist Bryan Jersky: The facts about Northampton school meals

Guest columnist Bryan Jersky: The facts about Northampton school meals Butch Garrity: Honor public safety telecommunicators this week

Butch Garrity: Honor public safety telecommunicators this week Jim Reis: Support for banning renter-paid broker fees

Jim Reis: Support for banning renter-paid broker fees Martin Konowitch: Is this what America wants?

Martin Konowitch: Is this what America wants?