Around Concord: Eagle Pond Farm, its literary inhabitants, and the nonprofit preserving their legacy

| Published: 03-31-2025 10:00 AM |

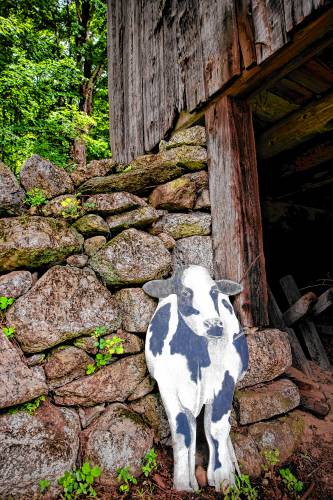

The white farmhouse, built at the start of the 19th century, sits tucked into a grassy knoll off a bend in Route 4 with Mount Kearsarge standing watch in the distance. As you drive down the road you’d never know the richness of the history surrounding you until long after the porch and green shutters become a speck in the rearview mirror.

Literary couple Donald Hall and Jane Kenyon breathed life into the house at Eagle Pond Farm in the decades they lived and wrote there. Now, seven years after Hall’s death and 30 years after Kenyon’s, their poetry still lingers within the walls of their Wilmot home.

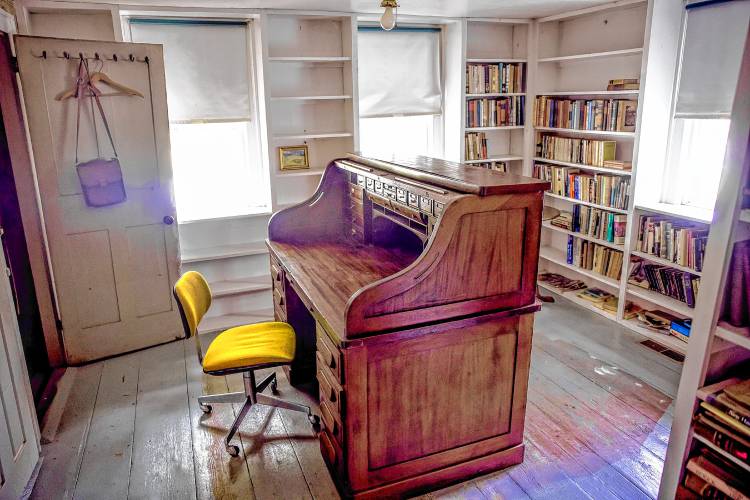

“The real spirit of the house is still there and you can feel it in the room,” said poet Laurie Zimmerman, who enjoyed a close friendship with the couple. “When you are there, you come into a place where creativity and thought and the nature of the past, in a good way, envelops you. It’s very conducive to writing and to people who want to just soak that in.”

In his nearly nine decades of life, Hall wrote more than 50 books spanning many forms and genres, including poetry, children’s literature, memoir, essays, and more. He served as the first poetry editor of the Paris Review from 1953 to 1961 and was the 14th U.S. poet laureate. Hall’s work includes the poem-turned-children’s book “Ox-Cart Man,” and the poetry collections “Exiles and Marriages,” “Kicking the Leaves,” “The Happy Man,” “Without: Poems” and “The Painted Bed.” He wrote often about Jane and their life together. Some of his other poems feature baseball, one of his great passions beyond writing.

Kenyon, who did not grow up in New England but made the landscape her home, penned four poetry collections in her 47 years of life: “From Room to Room,” “The Boat of Quiet Hours,” “Let Evening Come,” and “Constance.” She also translated from Russian “Twenty Poems of Anna Akhmatova.” Kenyon’s work carried a seriousness and precision to it, as well as a confluence with nature. She was New Hampshire’s poet laureate at the time of her death in 1995.

The work of Hall and Kenyon illuminated daily life on the 160-acre farm with acute observations and a sense of constantly discovering something exceptional in the ordinary.

“They were writing there at the farmhouse and seeing the same things, because a lot of the poetry talks about similar stuff, the farmhouse itself and their pets and nature growing around their house, but they present it in such different ways,” said musician Graham Sobelman, who has spent much of the last decade transforming Kenyon’s and, more recently, Hall’s, poetry into songs.

The pair met when Hall was teaching at the University of Michigan, where Kenyon was a student. They fell in love and married in 1972, moving several years later to Hall’s grandparents’ farm, a place he’d grown up visiting. The farmhouse became not only their home but one of the greatest sources of inspiration for their writing. Throughout their 23 years of marriage they traveled the world together, wrote countless poems, and forged a community of neighbors and writers in the Kearsarge region.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Hall chronicled Jane’s illness and death from leukemia in the mid ‘90s, channeling his grief into page upon page of heart-wrenching stanzas. He continued to live in the house they had shared for more than two decades afterward, forging ahead in life and literature until he died at 89, three months before his 90th birthday.

To many in the world of poetry, Hall and Kenyon represented larger-than-life literary personas – two brilliant minds who garnered countless accolades both intimidating and impressive. But to their loved ones, they were simply Don and Jane, the couple who lived in the three-story white Cape off Route 4.

“They were friends of my heart and soul and neighbors. Aside from their celebrity and their amazing work, they have an abiding place in my heart,” said Mary Lyn Ray, founder and president of At Eagle Pond, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the couple’s home and land.

Following Hall’s death in 2018, the farm went on the market, with all its belongings put up for auction the next year. When Ray, who keenly felt the couple’s absence, heard of the impending sale, she called Lynne Monroe, a friend who worked in historic preservation.

“We have to do something,” Monroe told Ray, so they devised a plan.

Monroe and her husband, Frank Whittemore, purchased the farm before it could be sold to other buyers. Several friends and neighbors banded together to buy back as many items as they could at the two auctions.

“We weren’t expecting to create a nonprofit,” Ray said. “We simply wanted to keep together the belongings that best told the story of Jane and Don.”

It quickly became clear the artwork and furniture they had salvaged needed to remain in its original home. Thus formed At Eagle Pond Inc., an organization dedicated to preserving the legacy of Hall and Kenyon, caring for the house and its land, and creating a space where writers can come in search of inspiration.

“What we’re hoping is that enough remains and enough can be brought back or closely substituted to evoke what Don’s and Jane’s days here were like, and what inspired their work. But even if we tried, we couldn’t reconstruct exactly what was here,” Ray said.

Since At Eagle Pond formed in 2019, some people who purchased items from the house have donated them to the nonprofit. While the farm can’t ever be what it was during the couple’s lifetimes, the organization hopes for new creativity to blossom in the space where such literary legacies were formed.

“It’s a natural place for that to be able to happen and to serve the community in that way,” said Zimmerman, who sits on the board of At Eagle Pond. “To have writing events, whether they’re residencies, workshops, or readings, would be so great.”

The nonprofit has its sights set on fundraising to make necessary repairs before being able to welcome writers and artists in any large capacity. At Eagle Pond has held a few events there in recent years, including a writing workshop. Sobelman had the opportunity to stay in the house for a week in 2021 and visited again the next year. He described it as “a magical place.”

“Because their poetry often talks about everyday life cooking and sitting and talking, just being in those rooms felt like you were inside those poems,” he said.

Another goal of the nonprofit is to get the farm, which is already a Seven to Save property, listed under the National Registry of Historic Places, which would provide another layer of protection.

“I think we really need to have a sense of roots,” Monroe said of the importance of historic preservation. “There are a lot of us who care.”

As At Eagle Pond works toward creating a rich writing environment and artists’ retreat, the organization strives to build an endowment to sustain the farmhouse into the future.

“What really keeps me at it is knowing how much it matters to people, and not only people nearby, but also people far away,” Ray said. “It’s such a true way to speak of where poetry comes from, the place of poetry in our lives, and the way that poetry can grow from the seemingly ordinary and familiar.”

The organization holds Hall, Kenyon and their poetry at the forefront of its endeavors while recognizing that the space they’ve created – be it in the house they’ve saved and the belongings they’ve rescued, or in the emptiness where beloved paintings once hung and books filled the shelves – will guide them toward the goal of preserving this place of poetry for coming generations.

“That same preservation is also about giving voice to the larger memory of the way life was lived in much of New Hampshire and northern New England until very recently — keeping story and meaning in what remains, elsewhere too, of that historical landscape,” Ray added.

To learn more about Hall, Kenyon and the nonprofit, visit ateaglepond.org

Rachel Wachman can be reached at rwachman@cmonitor.com