Balancing solar with farms and forestland: Experts tout middle way in picking sites

|

Published: 01-24-2024 5:44 PM

Modified: 01-25-2024 12:02 PM |

AMHERST — As debate continues over how best to develop solar throughout the state to help meet an ambitious net-zero emissions goal, representatives from Mass Audubon and Harvard Forest are touting a recently completed report that details how solar and forestland can co-exist in Massachusetts.

Or, pulling the words straight from the “Growing Solar, Protecting Nature” study, “We can have our forests, working lands, and solar, too.”

Representatives from Mass Audubon and Harvard Forest, a long-term ecological research site and an academic department at Harvard University, are in the middle of a statewide tour to discuss the report’s findings and policy recommendations. The tour stopped in Amherst on Monday night.

The report finds that it is possible for Massachusetts to meet its ambitious goals for clean electricity and net-zero emissions by 2050, while also protecting valuable natural and working landscapes.

“The results are incredibly promising: with the right policies, deliberate advance planning, and new incentives for protecting nature, we can achieve both outcomes,” the report’s executive summary states. “And the moment to pivot from current solar siting practices to those that protect natural and working lands is now.”

State Sen. Jo Comerford kicked off Monday’s event before about 30 people at the Bangs Community Center by saying that the state must find a way forward that allows for an “unbelievable uptick in renewable energy,” while maintaining current levels of carbon sequestration in natural and working lands.

“When we’re forced to think of these as a dichotomy in where we can’t have one or the other, we’re offered a faulty choice,” she said.

Experts who did the research for the “Growing Solar, Protecting Nature” are encouraged with its results, assuming that some of its policy recommendations are adopted.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

“We started this research and we had no idea if we could reach the solar targets and still be able to protect our most important natural and working lands. And so this felt a little risky,” said Jonathan Thompson of Harvard Forest. “I’m a professional ecologist, which means I’m in the business of bad news, but here, finally, this feels to me like a win-win.”

Thompson and Michelle Manion, vice president for policy and advocacy at Mass Audubon, outlined two potential scenarios of solar installation that preserve critical Massachusetts forests.

“We wanted to do this forward-looking projection to say, let’s look at continuing doing exactly what we’ve been doing for the last decade, which is really letting the developers decide sort of the footprint where the solar goes,” Manion said, “and then let’s look at some other scenarios where we kind of shift where that ground-mount solar in particular goes. And what if we can steer that to other places that have already been developed, but would not be as intrusive in the forest?”

Since 2010, ground-mount solar has displaced at least 1,800 acres of high biodiversity lands such as healthy forests and nearly 1,300 acres of farmland in Massachusetts. By 2050, the combined losses of farmland and high biodiversity lands would reach about 9,400 and 22,800 acres, respectively, under current development patterns, the report found.

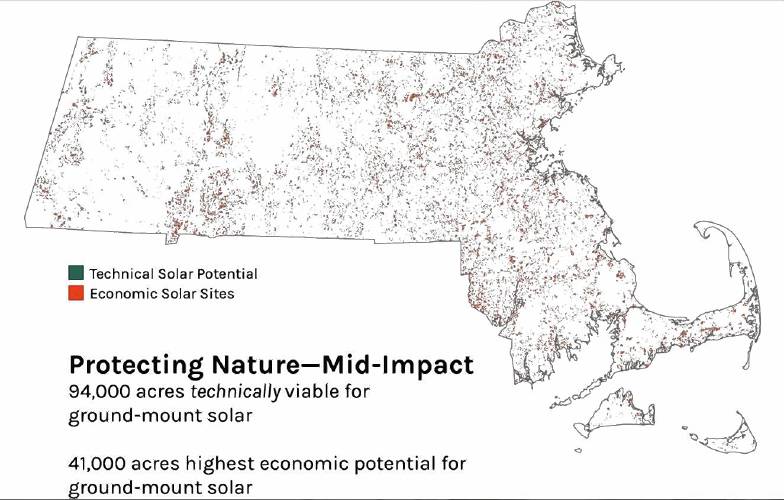

The report presents three scenarios: the current siting path that continues patterns of installation and disregards forest preservation, and two other scenarios — dubbed mid- and low-impact — that protect natural ecosystems, biodiversity and prime farmland to varying levels while still accommodating ground-mount solar.

Under the current siting scenerio 1.2 million acres of land is available for potential for solar development. Of the 1.2 million acres, only 51,000 to 142,000 acres are economically viable for ground-mount solar. In conjunction with other types of solar installations, this model could theoretically generate 25 gigawatts of energy by 2050, only 2 gigawatts off from the state’s 27-gigawatt goal.

“But that’s where we would ‘plus up’ through using state policy and state incentives to get even more (energy),” Manion said.

Instead of allowing solar projects on 1.2 million acres under the current trajectory, the mid-impact scenaro would limit such development to 94,000 acres, and calls for ramping up solar development of the urban landscape such as rooftops, parking lots, golf courses, and more. Of the 94,000 acres, 3,000 to 5,000 are in Hampshire County.

This model creates 21 gigawatts by 2050, but to get to the state’s goal of 27 gigawatts, Manion noted that efforts to lower soft costs, like permitting, labor, approvals and inspections, can increase the number of solar projects.

“We don’t want to get rid of inspections. We want quality systems. But you know, town by town permitting of solar, let’s figure out how to how to streamline that, for example,” she said.

While many sites identified in the mid-impact scenario are smaller and more expensive to develop efficiently than larger solar arrays, Manion warns that losing forestland, the state’s best carbon sequestration sink, comes at a much higher price.

The report discounts the low-impact scenario, which would prohibit solar development in any forest, floodplain or hurricane zone.

“The protecting nature, low-impact — which we know is a really restrictive scenario, and we don’t necessarily consider to be realistic — but it’s a kind of a cool boundary analysis to see,” Manion said.

The “Growing Solar, Protecting Nature” report concludes with policy recommendations in three areas: energy incentives and policies; state and local planning and community outreach; and policies specifically focused on protection of forest carbon, biodiversity and productive farmlands.

Among the recommendations are:

■ Stop state incentives for large ground-mount solar on high biodiversity and other natural and working lands and reprogram funds toward solar on low-impact lands and the built enviornment.

■ Invest in approaches to reduce soft costs of solar projects, such as a statewide permit for solar on the built enviornment and low-impact lands.

■ Conduct a statewide land use plan for multiple needs including clean energy infrastructure, transportation and affordable housing.

After the presentation, Stephanie Ciccarello, director of sustainability for Amherst, and Dwayne Breger, director of energy extension at UMass, joined Thompson and Manion in a panel. Breger discussed a solar planning tool kit for rural communities to better identify solar sites and gather community input in solar developments. Ciccarello touched on some guidelines developed by the solar bylaw working group for solar arrays on agricultural land.

“We need to grow the amount of solar and we need to do it by siting in places that don’t impact (important forest) and there are ways to do it,” he said. “It’s a false choice to say it’s either solar or nature — we can really have both and we just need to think so slow and smart about it.”

Emilee Klein can be reached at eklein@gazettenet.com.

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield Area briefs: Mount Holyoke’s Trailblazers of Color conference; Holyoke Library to host annual mini golf and games; Westfield State launches paramedic program

Area briefs: Mount Holyoke’s Trailblazers of Color conference; Holyoke Library to host annual mini golf and games; Westfield State launches paramedic program  Putting themselves on the line: Activists say nonviolent protests focus attention, inspire others, drive change

Putting themselves on the line: Activists say nonviolent protests focus attention, inspire others, drive change Legislation inspired by a Leverett family allows school bus monitoring systems

Legislation inspired by a Leverett family allows school bus monitoring systems