Aging With Adventure: The challenge of caring

| Published: 02-28-2025 10:20 AM |

I made a mistake.

I took a hiatus from writing in this space about aging with adventure because I thought I was taking a hiatus from adventure. Boy, was I wrong.

I errantly thought that spending more than a year caring for my elderly mother in her final time on earth was taking me away from adventure. I am honored to have enabled my mother’s final days spent at home — not her home, but my sister’s private home — instead of in a public or private nursing facility.

My mother, Aileen, was one of the good ones, a strong, generous, compassionate woman in the old style — modest, unassuming and honest in all she did, including raising her six children (within seven years) completely on her own. Aileen was an additive to the world, and her death, on July 15, 2024, at age 91, robbed the world of a bright, inspiring presence. She might not be comfortable as the subject of a public article, but then, she was an outgoing person and if sharing her experience could help others, she’d probably support it.

I assumed, in taking on the role of her co-caretaker, I would temporarily preempt my semi-retirement modus operandi of striking out on great adventures.

To the contrary, what I learned from spending nearly two years co-caring for my aging mother is that end-of-life care is, indeed, every bit an adventure on many levels. And of course, it’s certainly about aging.

So allow me to apologize for refraining from chronicling the experience in real time, here in a column about aging with adventure, for what others, engaged in or soon facing similar adventures (i.e., every single one of us), might have learned along the way.

To explain: I refer to my caretaking of my mother as an adventure, and I deeply intend that definition. Adventure, as I view it and have addressed it here, is not limited to exciting travel excursions or thrilling feats. My definition of adventure entails four components: challenge, risk, education and movement (virtual movement counts).

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton Housing Authority boss placed on leave

Northampton Housing Authority boss placed on leave

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

UMass Chancellor Reyes outlines changes amid financial uncertainty under Trump administration

UMass Chancellor Reyes outlines changes amid financial uncertainty under Trump administration

Ready to roll on roads: Amherst priority list tees up $4.55M to rebuild some of town’s worst stretches

Ready to roll on roads: Amherst priority list tees up $4.55M to rebuild some of town’s worst stretches

UMass hockey: Minutemen fall to Western Michigan, 2-1, in Fargo Regional final

UMass hockey: Minutemen fall to Western Michigan, 2-1, in Fargo Regional final

Amherst School Committee OK’s budget with no classroom layoffs, but spending plan is $500K more than town recommends

Amherst School Committee OK’s budget with no classroom layoffs, but spending plan is $500K more than town recommends

My definition is intentionally broad because I believe life itself to be an adventure, the greatest adventure. Aging is certainly an adventure containing all four of my definitional elements. One engages in adventure pursuing a degree, going to kindergarten, leaving home, returning home, taking a trip, practicing an instrument, performing in front of people, going on a first date, getting married, getting divorced, retiring from a job … and caring for a loved one in their final days.

To qualify as an adventure, an activity must: 1) take on challenge and prompt us to overcome it; 2) involve at least a measure of risk and a threat of loss; 3) include gaining knowledge and opportunity to apply it further; and 4) employ movement of some kind — a shift from here to there, a change of scenery — whether it be strenuous, repetitious, minuscule, virtual or over great distance.

Sharing in the full-time care of my mother included all those conditions. It was as much of an adventure to me as was thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail, climbing Mount Fuji, riding my bike across the United States or raising two kids.

That said, first and foremost, the most indelible lesson I came away with from this transformative experience, this adventure of caretaking, is: Plan your end.

By the way, I don’t mean this — any of this — to sound or feel remotely morbid. Rather, my intention is purely practical, a means of providing modest assistance for all of us in easing the process of, at some point, an inevitability.

Here’s what I often say, and what I again recently told my neighbor, based on my experience: “If you don’t plan your own end, someone else will do it for you, and it may not be what you wanted.”

Before caring for my mother, I had no concept of this lesson. My end? Who wants to think about that, let alone plan it? But here’s the thing: It would have simplified many facets of the care process if we had discussed, forethought and put on paper some aspects of my mom’s final days and afterward.

A will, for one, is an easy and important step. My mother’s estate was modest and simple to process. But if one has any intention of what should become of their possessions once they depart, writing it down and notarizing it will help those sorting things out later.

Also, a living will, for many, can provide a huge assist. It’s a document in which you can specify all your preferences for certain scenarios, such as if something happens that renders you unable to express your desires. The more advanced medical technology becomes, and the more ways we devise for keeping our hearts beating and lungs breathing, the more essential a living will becomes.

In our experience, we also would have benefited from discussing some of what my mother envisioned for her final months. Most of us would probably say we would prefer to spend the end of our days in the company of loved ones, like our children. But not everyone is able to arrange that, and it carries connotations that all parties involved should be aware of.

I can say, caring for a parent, or anyone, as they age toward their final breath can be a massive, all-consuming responsibility. It’s emotionally turbulent, at times excruciating but with moments of intimacy, closeness and even joviality. It requires a deep well of strength, mentally and, progressively, physically.

Asking or expecting your children or someone else to take on that role is ideally a conversation that takes place when mental faculties are solid and sentient. At the very least, I argue, talking about the end with people you trust will yield information, perspective, and possibly practical details that will enhance the process when the time comes.

We should at least be aware of how our loved one feels about, or even knows about, different levels of care, like retirement homes, memory care units, public and private nursing homes, in-home; and what remaining at home or at your caretaker’s home will involve, for everyone. There may be some sacrifices in caretaking quality, for example.

Writing down how you prefer your final time on earth to proceed will let others know your desires and give them a basis on which to make their decisions for you instead of presuming.

This is related to the above point on planning and thinking ahead. But money is its own category because — there’s no other way to put it or get around it — the end of life costs money.

Though my sister and I were able to arrange our schedules to spend 20 hours a day with Aileen (24 on weekend days), we needed to hire private in-home care for four hours a day, just to squeeze out time for making a living. It was intense, but that four hours was vital, and costly.

My mother was able to save some money that we could use for this purpose. But her wisdom in raising six kids, who all contributed financially and in caretaking, also helped distribute some of the intensity.

Assistance programs like Medicaid/MassHealth help millions of people with care at this stage, but qualification criteria is very stringent. Despite my mother’s modest means, we didn’t qualify. Long-term care insurance can help in some cases as well, but be certain to shop around. There are many options, some of them not optimal or even legit.

The final arrangements, such as funeral or memorial service, burial, obituaries and any attorney services for probated estates, also cost money, likely starting in the low five figures, all summed up.

In the absence of riches, a set-aside account designated for end-of-life expenses would greatly lower the stress and ease the work of tending to such matters for those tasked with the job.

In our position of caring for our mother, my sister and I talked and commiserated with many others in similar situations, as well as with our invaluable nurses and caretaking professionals, about all of it. We heard stories about children being driven to the mental edge trying to take care of their parents, allowing their own self-care to flag. It’s a mistake.

Staying as healthy as possible while caring for your loved one is necessary. Yoga, meditation, exercise, a wise diet, whatever it takes — you have to maintain parts of yourself to get through it. Completely sacrificing your own life, as some do, is a recipe for burnout and breakdown.

It made a huge difference to walk outside with my mother every day I spent with her. She loved walking, but even when it came time for a wheelchair, it always had a positive effect.

For that matter, the best thing we can do to invest in our eventual end of life is to take good care of ourselves all through it. Exercise and healthy diet, of course. But also, we must drink water all the time, especially as we age. Some estimates suggest that up to 50% of dementia is due to dehydration. And do things that make you feel happy and fulfilled. High stress is a brutal life-shortener.

My mother lived a great life, as she often agreed in her final months. She traveled a lot, she was loved broadly, she welcomed new experiences and she had a ton of fun and adventure. She laughed and joked all the time, including when things were tough, and taught her offspring the value of laughter.

That may be the most important lesson of all. Live life fully. At the end, no one wants to be burdened with thoughts of things they could have done or tried, but didn’t.

My mother’s example was priceless. Watching her life, I learned how to get a lot out of this time on earth. Caring for her at the end taught me to conceptualize the entirety of life, to not shy away from thinking ahead, and set plans for approximating an exit as close to my terms as possible when the time comes.

Importantly, it underscored the value of adventure and regarding all of this as adventure, including assisting my mother’s final days. In honor of my mother, I will resume my monthly narrations of forays near and far, and perspectives on aging with adventure.

Eric Weld, a former Gazette reporter, is the founder of agingadventurist.com.

Historic speech echoes two centuries later: ‘A Light Under the Dome’ recalls the first American woman to speak to a legislative body

Historic speech echoes two centuries later: ‘A Light Under the Dome’ recalls the first American woman to speak to a legislative body ‘His notes will linger forever’: Remembering Young@Heart accordionist and Springfield College professor Chris Haynes

‘His notes will linger forever’: Remembering Young@Heart accordionist and Springfield College professor Chris Haynes Valley Bounty: And on that farm she had a bit of everything: Little Brook Farm in Sunderland is a labor of love for farmer Kristen Whittle

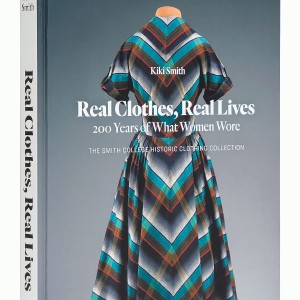

Valley Bounty: And on that farm she had a bit of everything: Little Brook Farm in Sunderland is a labor of love for farmer Kristen Whittle Women’s history told through clothing: Shelburne Falls Area Women’s Club to host ‘Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore’ author, April 9

Women’s history told through clothing: Shelburne Falls Area Women’s Club to host ‘Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore’ author, April 9