Latest News

‘Delightful’ Northampton store shopping guide Jane Hertz, 88, seeking next gig

NORTHAMPTON — With the closure of Ten Thousand Villages in Northampton this month, longtime employee and beloved community member Jane Hertz, 88, doesn’t plan to simply give up the community connections and meaningful work she found through the store.

Photo: Spring calling

Most Read

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

State senators organize Trump defense: Comerford a leader on Response 2025 initiative

State senators organize Trump defense: Comerford a leader on Response 2025 initiative

Five UMass Amherst students have visas, student status revoked

Five UMass Amherst students have visas, student status revoked

Hatfield Select Board removes elected Housing Authority member

Hatfield Select Board removes elected Housing Authority member

Editors Picks

A Look Back: April 7, 2025

A Look Back: April 7, 2025

Amherst can’t decide where it is: Is town center uptown or downtown?

Amherst can’t decide where it is: Is town center uptown or downtown?

Area briefs: Northampton to celebrate Earth Day with tree plantings; Shutesbury Dems to caucus; Three County Fair food drive; HCC’s free clean energy jobs program

Area briefs: Northampton to celebrate Earth Day with tree plantings; Shutesbury Dems to caucus; Three County Fair food drive; HCC’s free clean energy jobs program

‘Art in the Age of Human Impact’: New exhibition at UMass explores complex relationship between humans and nature

‘Art in the Age of Human Impact’: New exhibition at UMass explores complex relationship between humans and nature

Sports

UConn women's basketball team captures 12th national title in dominant win over South Carolina

TAMPA, Fla. — UConn is back on top of women’s basketball, winning its 12th national championship by routing defending champion South Carolina 82-59 on Sunday behind Azzi Fudd’s 24 points.

On The Run with John Stifler: Fast walkers

On The Run with John Stifler: Fast walkers

Opinion

Guest columnist John Saveson: Use your spending power for the planet

Guest columnist John Saveson: Use your spending power for the planet

Betty Ussach-Schwartz: The greatest grift of all

Betty Ussach-Schwartz: The greatest grift of all

Jerry Halberstadt: Problems at Northampton Housing Authority seen in many housing programs

Jerry Halberstadt: Problems at Northampton Housing Authority seen in many housing programs

Susan Lantz: Truth-telling

Susan Lantz: Truth-telling

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Business

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

NORTHAMPTON — After more than five years of sitting vacant, the site of the old Faces store at 175 Main St. will finally have a new occupant, one that’s already established itself as a downtown mainstay of downtown.

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Making News in Business, April 4

Making News in Business, April 4

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Arts & Life

Here to help the community’s artists: Human Scale Art Space aims to advance visual arts in the Pioneer Valley

It’s not uncommon for a small nonprofit not to have a physical space. It is, however, ironic when that nonprofit itself is called Human Scale Art Space.

Obituaries

Karen Dennett Tripp

Karen Dennett Tripp

Haydenville, MA - Karen Dennett Tripp passed away on Mar 9, 2025, in Leonardtown, MD with her son at her side. She was 85 years old. Born on Sep. 12, 1939, in Provo, UT, to Elwood and Nettie Hardy Dennett, Karen lived a life marked by ... remainder of obit for Karen Dennett Tripp

Lucy Claire Henchey

Lucy Claire Henchey

Southampton, MA - Lucy Claire Henchey, 92, of Southampton passed away peacefully on April 1, 2025. Lucy was born on January 28, 1933, in Easthampton, MA, the daughter of Alfred Briere and Rose Leduc Briere. Lucy attended Notre Dame Scho... remainder of obit for Lucy Claire Henchey

Olive Arel

Olive Arel

Sebastian , FL - Olive (Loiselle) Arel, aged 93, passed away peacefully on March 25, 2025, at the VNA Hospice House in Vero Beach, FL. Born on April 20, 1931, in Northampton, MA., she was the daughter of the late Oliver and Annabelle (M... remainder of obit for Olive Arel

Everett Lennox Reed Jr.

Everett Lennox Reed Jr.

Everett Lennox Reed, Jr. Amherst, MA - Everett Lennox Reed, Jr., 98, passed away on February 24, 2025. Everett is survived by Ken Reed and Ann Marie Lucey (son and daughter-in-law; Northampton MA), Dave and Sakun Reed (son and daughter-i... remainder of obit for Everett Lennox Reed Jr.

COVID 5 years later: Is Massachusetts prepared for another pandemic?

COVID 5 years later: Is Massachusetts prepared for another pandemic?

Belchertown residents worry $3.3M override request is too high

Belchertown residents worry $3.3M override request is too high

Hadley TM to consider zone changes to allow for more variety of senior housing

Hadley TM to consider zone changes to allow for more variety of senior housing

Southampton resident new interim pastor at North Congregational Church in New Salem

Southampton resident new interim pastor at North Congregational Church in New Salem

Amherst’s Ryan Leonard scores first career NHL goal in Capitals’ win over Blackhawks

Amherst’s Ryan Leonard scores first career NHL goal in Capitals’ win over Blackhawks

Advocates explore ways to persuade House to legalize overdose prevention centers

Advocates explore ways to persuade House to legalize overdose prevention centers

Amherst drawing up plans for area north of UMass campus that could triple the number of apartments currently there

Amherst drawing up plans for area north of UMass campus that could triple the number of apartments currently there

HS Roundup: Ella Schaeffer, South Hadley softball blanks Easthampton 11-0 (PHOTOS)

HS Roundup: Ella Schaeffer, South Hadley softball blanks Easthampton 11-0 (PHOTOS) High school softball preview 2025: Hampshire Regional returns plenty of talent

High school softball preview 2025: Hampshire Regional returns plenty of talent  HS Roundup: Keller Mahoney’s six-point day lifts Northampton boys lacrosse over Lenox, 9-4, in season opener

HS Roundup: Keller Mahoney’s six-point day lifts Northampton boys lacrosse over Lenox, 9-4, in season opener

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Paving over historic beauty: A history of the White House Rose Garden that Trump plans to rip up

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Paving over historic beauty: A history of the White House Rose Garden that Trump plans to rip up Valley Bounty: Nothing sweeter than sourcing local: Lemon Bakery in Amherst is a small, seasonal, from-scratch operation

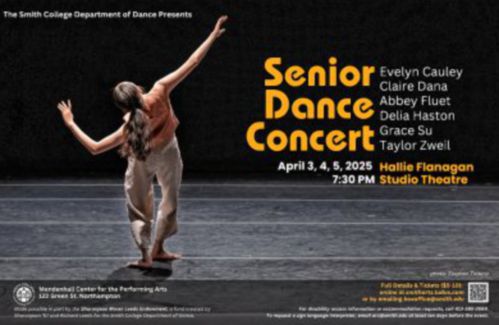

Valley Bounty: Nothing sweeter than sourcing local: Lemon Bakery in Amherst is a small, seasonal, from-scratch operation Arts Briefs: Power of Truths Fest in Florence, dance at Smith, jazz at UMass, and more

Arts Briefs: Power of Truths Fest in Florence, dance at Smith, jazz at UMass, and more Speaking of Nature: Stinky signs of spring: Skunk cabbage is eye candy after months of winter landscape

Speaking of Nature: Stinky signs of spring: Skunk cabbage is eye candy after months of winter landscape