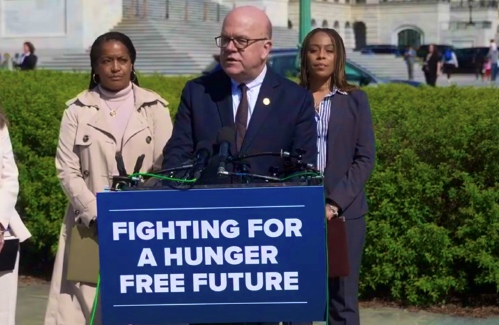

McGovern co-sponsors bill that aims to stop ‘backdoor’ cuts to SNAP benefits

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Accusing his Republican colleagues in Congress of being “too scared to stand up to their leadership,” namely, President Donald Trump and Elon Musk, U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern is co-sponsoring a new bill designed to block “backdoor” cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP.)

Shutesbury reviewing how to improve safety on Lake Wyola in wake of accident last summer

SHUTESBURY — While no ban on motorboats on Lake Wyola is being contemplated, a serious accident that injured a boater last June has prompted a review of the current bylaw governing use of the 128-acre body of water, which some residents say should be modified to enhance safety, while others say safety is largely a matter of personal responsibility.

Most Read

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Northampton schools probe staff response to student’s unfulfilled IEP

Northampton schools probe staff response to student’s unfulfilled IEP

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Sabadosa, Velis push for state endometriosis task force to raise awareness about little-known illness

Sabadosa, Velis push for state endometriosis task force to raise awareness about little-known illness

Editors Picks

A Look Back, April 4

A Look Back, April 4

Photos: Heavy lift in Easthampton

Photos: Heavy lift in Easthampton

Arts Briefs: Power of Truths Fest in Florence, dance at Smith, jazz at UMass, and more

Arts Briefs: Power of Truths Fest in Florence, dance at Smith, jazz at UMass, and more

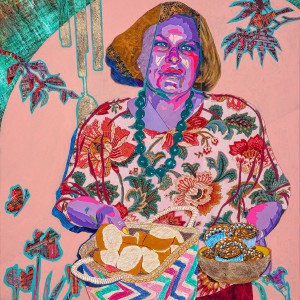

‘Art in the Age of Human Impact’: New exhibition at UMass explores complex relationship between humans and nature

‘Art in the Age of Human Impact’: New exhibition at UMass explores complex relationship between humans and nature

Sports

HS Roundup: Keller Mahoney’s six-point day lifts Northampton boys lacrosse over Lenox, 9-4, in season opener

Keller Mahoney matched Lenox’s output by himself Thursday afternoon, as he tallied four goals and added two assists in a dominant showing for the Northampton boys lacrosse team. The Blue Devils used his offensive outburst to cruise past the Millionaires, 9-4, on their home turf and claim a victory in their season opener.

Opinion

Guest columnist Teresa Amabile: Undermine education, undermine our future

Guest columnist Liz Brown: Abortion care is health care

Guest columnist Liz Brown: Abortion care is health care

D. Dina Friedman: Jewish group decries ICE’s crackdown on freedom of speech

D. Dina Friedman: Jewish group decries ICE’s crackdown on freedom of speech

Henry Lappen: Tango is alive and well in the Valley

Henry Lappen: Tango is alive and well in the Valley

Carolyn Cushing: Stop perpetuating dehumanization

Carolyn Cushing: Stop perpetuating dehumanization

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Business

Long-vacant former Faces spot in Northampton gets new tenant

NORTHAMPTON — After more than five years of sitting vacant, the site of the old Faces store at 175 Main St. will finally have a new occupant, one that’s already established itself as a downtown mainstay of downtown.

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Here come the sweetness: Four new businesses prepping to open in downtown Northampton

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Area property deed transfers, April 4

Making News in Business, April 4

Making News in Business, April 4

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Hopeful buyers emerge for Magic Wings butterfly conservatory in South Deerfield

Arts & Life

Here to help the community’s artists: Human Scale Art Space aims to advance visual arts in the Pioneer Valley

It’s not uncommon for a small nonprofit not to have a physical space. It is, however, ironic when that nonprofit itself is called Human Scale Art Space.

Obituaries

Elizabeth Ann Fischer

Elizabeth Ann Fischer

Northampton, MA - Elizabeth Ann Fischer, 89, passed away March 22, 2025 at the Linda Manor Nursing Home in Leeds MA. She was born June 30, 1935 in Northampton. Elizabeth, a dedicated mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, was a tale... remainder of obit for Elizabeth Ann Fischer

Maija Z. Lillya

Maija Z. Lillya

Amherst, MA - Maija Zadins Lillya passed away peacefully at home on March 21, 2025, surrounded by family. Maija was born in 1939 in Smiltene, Latvia, during the brief period of independence between world wars. In November 1944 her famil... remainder of obit for Maija Z. Lillya

Raymond Kenyon Bradt Jr.

Raymond Kenyon Bradt Jr.

[IMAGE]Raymond Kenyon "Ken" Bradt, Jr. Amherst, MA - Raymond Kenyon Bradt, Jr., died at Cooley Dickinson Hospital, in Northampton, MA, on February 10, 2025, at age 82. His partner and the hospital chaplain were by his side and Bach's cello ... remainder of obit for Raymond Kenyon Bradt Jr.

Gerard Houle

Gerard Houle

Gerard (Jerry) Houle Easthampton, MA - Gerard (Jerry) R Houle, 93 of Easthampton, passed away on March 31. Jerry was born on December 1,1931 in Holyoke, to the late Alfred and Jeannette (Loiselle) Houle. Jerry spent his early years in C... remainder of obit for Gerard Houle

Hatfield Select Board removes elected Housing Authority member

Hatfield Select Board removes elected Housing Authority member

Final interviews set for Granby school superintendent candidates

Final interviews set for Granby school superintendent candidates

Political analyst to discuss Middle East, new book in western Mass talks

Political analyst to discuss Middle East, new book in western Mass talks

Scaled-back DPW project heads to Hadley voters at Town Meeting

Scaled-back DPW project heads to Hadley voters at Town Meeting

UMass basketball: Jayden Ndjigue, Daniel Hankins-Sanford will return to Minutemen next season

UMass basketball: Jayden Ndjigue, Daniel Hankins-Sanford will return to Minutemen next season

Trump tariffs crater markets worldwide

Trump tariffs crater markets worldwide

Granby voters to consider $10M override for old West Street School project

Granby voters to consider $10M override for old West Street School project

A flash point over gun control: Can Massachusetts’ strict firearms law survive the 2026 ballot?

A flash point over gun control: Can Massachusetts’ strict firearms law survive the 2026 ballot?

Three vying for two Hadley Select Board seats in May 20 election

Three vying for two Hadley Select Board seats in May 20 election

HS Roundup: Frontier baseball blanks Hopkins, 5-0, improves to 3-0 this season (PHOTOS)

HS Roundup: Frontier baseball blanks Hopkins, 5-0, improves to 3-0 this season (PHOTOS) UMass hockey: Minutemen lose O'Hara, Suniev, Connors early to NHL deals

UMass hockey: Minutemen lose O'Hara, Suniev, Connors early to NHL deals Amherst’s Ryan Leonard makes NHL debut for Washington Capitals in 4-3 win over Bruins in Boston

Amherst’s Ryan Leonard makes NHL debut for Washington Capitals in 4-3 win over Bruins in Boston UMass basketball: Akil Watson, Marqui Worthy join group of Minutemen entering transfer portal

UMass basketball: Akil Watson, Marqui Worthy join group of Minutemen entering transfer portal Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Paving over historic beauty: A history of the White House Rose Garden that Trump plans to rip up

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Paving over historic beauty: A history of the White House Rose Garden that Trump plans to rip up Valley Bounty: Nothing sweeter than sourcing local: Lemon Bakery in Amherst is a small, seasonal, from-scratch operation

Valley Bounty: Nothing sweeter than sourcing local: Lemon Bakery in Amherst is a small, seasonal, from-scratch operation Speaking of Nature: Stinky signs of spring: Skunk cabbage is eye candy after months of winter landscape

Speaking of Nature: Stinky signs of spring: Skunk cabbage is eye candy after months of winter landscape Historic speech echoes two centuries later: ‘A Light Under the Dome’ recalls the first American woman to speak to a legislative body

Historic speech echoes two centuries later: ‘A Light Under the Dome’ recalls the first American woman to speak to a legislative body